For decades, environmental discourse in Lebanon — and much of the world — cast the economy as the villain. Growth meant pollution. Industry meant destruction. Capital was seen as inherently incompatible with conservation. Caught in this zero-sum framing, NGOs and environmental activists responded by treating nature as a stand-alone silo: isolated, underfunded, and eternally dependent on external aid.

But what if the real solution isn’t fighting the economy, but transforming it? What if the road to environmental restoration in Lebanon runs not around markets, but straight through them — redesigned with circularity, regeneration, and equity at their core?

The Silo That Failed: Environmentalism Without Economics

Lebanon’s environmental response has long suffered from fragmentation. From recurring waste crises to devastating wildfires, efforts on the ground have been reactive, isolated, and often short-lived. Projects operate without national frameworks, sustained financing, or economic incentives. They survive off aid, not alignment.

Even within the environmental community, fragmentation prevails. Competition over funding and visibility often undermines the shared goal of ecosystem restoration. Impact becomes a matter of reach metrics, not resilience outcomes.

Why? Because the environment has been treated as a cost—not a contributor. Municipalities manage floods with no climate budget. NGOs plant trees without a forest policy. Activists campaign against plastic while industry dumps with impunity. We’re pruning branches while ignoring the roots.

It’s time to build systems designed for resilience, and regeneration.

Enter the Circular & Blue Economies

Models like the circular economy, the blue economy, and regenerative finance mark a departure from extraction toward regeneration. They present a design where value is replenished—not consumed.

Imagine:

Fisheries that protect marine ecosystems while boosting coastal incomes

Solar grids that decentralize energy and create rural jobs

Recycling hubs that transform waste into value chains

Green building retrofits that cut emissions and employ youth

Cities designed to promote public health and clean air

These aren’t pipe dreams. They’re happening worldwide—from Morocco’s renewable transition to Indonesia’s mangrove-based aquaculture. Lebanon has the human capital and ecological diversity to do the same. But only if the economy takes the front seat.

From Subsidy Drains to Incentive Chains

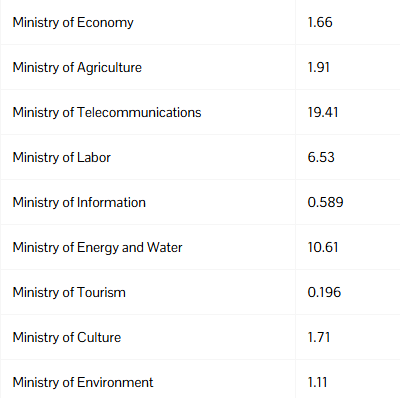

According to Lebanon’s 2024 budget, over $119 million in energy subsidies continue to support fossil fuel consumption—about 2.4% of the national budget. In contrast, less than 0.2% goes to environmental protection or climate resilience (BlomInvest)

Figure 1: Budget Expenditures by Lebanese Government to Ministeries 2024 - Trillion Lebanese Lira

A restructured economic model could:

Incentivize green behaviors through carbon pricing, water metering, and smart energy tariffs

Lower the import bill by investing in local renewable energy

Boost exports and lower industrial costs via circular production models

Build new value chains in green sectors

Redirect harmful subsidies toward renewable energy, agroecology, and waste innovation

Attract untapped global climate finance—with over $100 billion available annually through mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund (World Bank Climate Finance Brief, 2024)

Incentives are not just financial. They’re behavioral. When people see that sustainability pays, they adopt it faster.

The Nexus Model: Where Economic Reform Becomes Environmental Strategy

Siloed environmentalism is no longer fit for purpose. In an era of ecological collapse and fiscal constraint, Lebanon must retire the idea that forests, rivers, and cities are managed in isolation.

Figure 2: Ellen Macarthur Circular Economy Model

We need economic convergence: a model where natural assets are managed based on their productive functions and economic flows.

A tree is not just shade. It’s a carbon sink, a soil protector, and an ecotourism asset.

A river is not just water. It’s a transport channel, irrigation source, and hydro input.

A port is not just trade infrastructure. It’s a blue economy hub and a resilience multiplier.

This is the new environmental economics: where economic reform becomes the engine of ecological recovery.

Lebanon’s Choice: Build Forward or Collapse Back

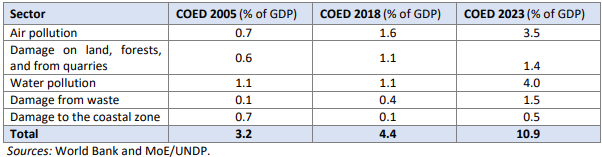

According to the World Bank, climate-related damages could reduce Lebanon’s GDP by up to 2% annually by 2040. That’s nearly $2.5 billion in losses each year across agriculture, tourism, and infrastructure (World Bank & L'Orient le Jour)

Figure 3: Cost of Environmental Degradation to GDP, 2024

But a green transition could deliver:

50,000 new green jobs in sectors like solar, recycling, sustainable transport, and nature-based tourism

1,400 MW of solar PV capacity added in 2024 alone—nearly 50% of Lebanon’s official energy output

Ports powered by solar, qualifying for green shipping incentives and lowering operating costs

30% renewable energy penetration, supported by rising imports of solar panels (Pvknowhow)

Reversal of deforestation, erosion, and biodiversity loss

Watershed restoration to protect irrigation and hydropower systems, such as the Litani River’s severely depleted flow

This isn’t a policy memo. It’s a survival blueprint. We must shift from project-based charity to investment-grade ecosystems.

Figure 4: Sustainable Businesses Model

Final Word: Stop Treating the Environment Like a Charity. It’s a Portfolio.

Lebanon doesn’t need more tree-planting campaigns without water networks. It doesn’t need more waste bins in cities with no recycling markets. And it certainly doesn’t need speeches about climate justice without fiscal backing.

What it needs is a new social contract—one where environmental sustainability is not a byproduct of economic reform, but its central mechanism.

Because the only way to save the environment... is to rethink the economy.

By Kareem Salameh, environmental researcher at enmaeya